Haskell: Difference between revisions

| Line 525: | Line 525: | ||

</syntaxhighlight> | </syntaxhighlight> | ||

And the answer was, it improves performance in the compiler - Sigh!!! | And the answer was, it improves performance in the compiler - Sigh!!! | ||

=Creating Type Classes= | |||

To create a type class you need to | |||

*Create a type class stating some behaviors | |||

*Make a Type instance of that Type Class with implementation of those behaviors | |||

Overloading | |||

*In Haskell Overloading is multiple implementations of function or value with the same name | |||

==Example of type class== | |||

The Eq is already defined but here is how it could work. It looks like we are just defining overloaded operators like C++ | |||

<syntaxhighlight lang="hs"> | |||

-- Define class | |||

class Eq a where | |||

(==) :: a -> a -> Bool | |||

(/=) :: a -> a -> Bool | |||

-- Here is our data type | |||

data PaymentMethod = Card | Cash | CC | |||

-- Create instance of our PaymentMethod | |||

Instance Eq PaymentMethod where | |||

-- == | |||

Card == Card = True | |||

Cash == Cash = True | |||

CC == CC = True | |||

_== _ = False | |||

-- /= | |||

Card /= Card = False | |||

Cash /= Cash = False | |||

CC /= CC = False | |||

_== _ = True | |||

</syntaxhighlight> | |||

Now this was easy but can be done better because we have repeated ourselves with the Not Equal bit. We use some called '''Mutual Recursion''', with is when we define the negative in terms of the positive and vice-versa. Probably wont remember but the name will allow me to google it but here is the improved version | |||

<syntaxhighlight lang="hs"> | |||

class Eq a where | |||

(==), (/=) :: a -> a -> Bool | |||

x /= y = not (x ==y) | |||

x == y = not (x /=y) | |||

-- Now we only need to define the positive as the compiler will infer the negative | |||

Instance Eq PaymentMethod where | |||

Card == Card = True | |||

Cash == Cash = True | |||

CC == CC = True | |||

_== _ = False | |||

-- Info for Eq class | |||

:i Eq | |||

type Eq :: * -> Constraint | |||

class Eq a where | |||

(==) :: a -> a -> Bool | |||

(/=) :: a -> a -> Bool | |||

{-# MINIMAL (==) | (/=) #-} | |||

... | |||

</syntaxhighlight> | |||

Because both function have the same type we can specify them in oneline. The '''not''' function which takes a boolean and returns the opposite. We can see running the info command for the Eq class we see the MINIMAL implementation is == or /= | |||

=Modules= | =Modules= | ||

Revision as of 22:04, 16 February 2025

Introduction

This is my first dip into Haskell, just felt like trying it. Haskell is a purely functional programming language. rather than a declarative language. I.E. it is a declarative language rather than imperative. With declarative, you tell the language what the thing is rather than how to do the thing.

Features

Lazy

Haskell is a programming lazy language and only evaluates on usage. E.g. only evaluates the first 10

let infiniteList = [1..]

take 10 infiniteList

Modules

Starting to look a lot like Lisp. This next bit shows how you can combine various functions of your own to produce and output

let double = x = x * 2

let increment x = x + 1

let doubleThenIncrement x = increment(double x)

doubleThenIncrement 10 -- Answer is 21

Statically Typed

With Haskell types are inferred

Hello World

Here we start with main and strange format but no curly brackets which is good.

main :: IO()

main = putStrLn "Hello World"

We build like gcc using

ghc hello.hs -o hello

Types

- Int, Integer e.g. 1

- Float, Double 21.3

- Chars e.g. 'S'

- Boolean e.g. True, False

- List e.g. [1,2,3], [True, False, True], elements must be of same type

- Tuple e.g. (1,2,3, "string, True)

Function Signature

With Haskell there are no variables as things are immutable. Therefore what look list variable declarations are actually more like consts and call definitions e.g.

name:: String

name = "Bob"

For functions with one argument this is straight forward

square :: Int -> Int

square v =v * v

But more arguments not a straight forward and seem to be declared like currying functions. Remember the last type is the result of the function

product :: Int -> Int -> Int

product x y = x * y

We can have a signature with no specific type. Haskell handles these polymorphic types

first :: (a, b) -> a

first (x, y) = x

The function must return value of type of a.

Notation

Not complicated just how the format operators

Prefix

We use the operator before the arguments. Note brackets around symbol operator

(+) 3 4 prod 3 4

Infix

We use the operator between the arguments. Note for non symbol, need back ticks

3 + 4 3 `prod` 5

Lists

We can assess lists using the double bang operator. e.g.

"abc" !! 1 -- b

[12,13, 16,18] !! 3 -- 18

-- Make a list

[3..5] -- [3,4,5]

-- Make a list with step

[3,5..13] -- [5,8,12]

-- Make an infinite list

[5..]

-- Take

take 3 [1,2,3,4] -- [1,2,3]

-- Concat with ++

[1,2] ++ [3,4] -- [1,2,3,4]

-- Make a list with letters

['a', 'c'...'f'] -- ["acdef"]

-- Null Length, sum and `elem`

Here are some more examples

let x = [1..10]

head x -- 1

tail x -- [2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10]

last x -- 10

init x -- [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9]

reverse x -- [10,9,8,7,6,5,4,3,2,1]

length x -- 10

take 5 (x) -- [1,2,3,4,5]

drop 6 (x) -- [7,8,9,10]

sum x -- 55

product x -- 3628800

elem 8(x) -- True Searches list

null x --- False

We also have words, unwords, lines and unlines to join and break text

Conditionals

If else

You must use the else as every function must return a value

main = do

let var = 23

if var `rem` 2 == 0

then putStrLn "Number is Even"

else putStrLn "Number is Odd"

Guards

Simple and easy to read

bookCategory :: Int -> String

bookCategory age

| age < 10 = "Children's book"

| age < 18 = "Teen book"

| otherwise = "Adult book"

main = do

print(bookCategory 5)

print(bookCategory 15)

print(bookCategory 25)

Pattern Matching

Again easy pezzy and I love pattern matching

-- Pattern Matching

coffeeType :: String -> String

coffeeType "Epresso" = "Strong and bold"

coffeeType "Cappuccino" = "Frothy and delicious"

coffeeType "Filter" = "Watery and weak"

coffeeType _ = "I have no idea what that is"

main = do

print(coffeeType "Epresso")

print(coffeeType "Cappuccino")

print(coffeeType "Filter")

print(coffeeType "Latte")

Case Expressions

Again easy pezzy

checkForZeroes :: (Int, Int,Int) -> String

checkForZeroes (0,_,_) = "First is zero"

checkForZeroes (_,0,_) = "Second is zero"

checkForZeroes (_,_,0) = "Third is zero"

checkForZeroes _ = "No zeros"

checkForZeroes(32,0,256) -- "Second is zero"

Let expressions

The word bind haughts me, it is like trying to remember Samuel L Jackson's name. Here is the tutors opening gambit

With in

func arg =

let <BIND_1>

<BIND_2>

in <EXPR that uses BIND_1 and/or BIND_2>

With where

func arg = <EXPR that uses BIND_1 and/or BIND_2>

where <BIND_1>

<BIND_2>

I have to say they are now speaking my language as this was the example which does look pretty pretty awful

hotterInKelvin :: Double -> Double -> Double

hotterInKelvin c f = if c > (f- 32) * 5/9 then c + 273.16 else (f - 32) * 5/9 + 273.16

hotterInKelvin 40 100 -- 273.16

Now we have this and I understand the BIND_1 or BIND_2 are just declared expressions for use with the in control

hotterInKelvin2 :: Double -> Double -> Double

hotterInKelvin2 c f =

let fToCelius t = (t - 32) * 5 / 9

cToKelvin t = t + 273.16

fToKelvin t = cToKelvin (fToCelius t)

in if c > fToCelius f then cToKelvin c else fToKelvin f

And using where approach

hotterInKelvin3 :: Double -> Double -> Double

hotterInKelvin3 c f =

if c > fToCelius f then cToKelvin c else fToKelvin f

where

fToCelius t = (t - 32) * 5 / 9

cToKelvin t = t + 273.16

fToKelvin t = cToKelvin (fToCelius t)

I prefer the where one because I can stop reading quicker but they said I would take time to workout and sometimes preference

More on Functions

High Order functions

Now I know more about signature and how to read them

applyTwice :: (a->a) -> a -> a

applyTwice f x = f (f x)

Make must more sense, as the signature shows

- the first argument is a function take a type a and returning a type a,

- the second a value of type a and

- the result is of type a

Built-in Map function

let increment x = x + 1

map increment [1,2,3] -- [2,3,4]

Built-in Filter function

And filter, loving the mod operation

let isEven n = n `mod` 2 == 0

filter isEven [2,3,4] -- [2,4]

Built-in Foldl function

Finally something new, foldl, i.e. apply operation start from position using array from left to right (lispy)

foldl (+) 0 [1,2,3,4,5] -- 15

Sort function and others

And now first use of libraries

import Data.List (sort)

sort [10, 2, 5, 3, 6, 7, 4, 8, 9, 1]

Other functions were zipWith, takeWhile, dropWhile

-- All

all even [1,2,4] -- False

any even [1,2,4] -- True

Lambda Expressions

This is a shortcut to writing unnamed function. We do this by

- specifying a back slash

- specifying arguments

- an arrow

- specifying body

print((\c -> c * 9/5 + 32) 25) -- 77.0

Precedence and Associativity

In Haskell the operators have a precedence, like looking at type with :t you can see this with :i (+). The higher the number the higher the precedence. If two have the same then then the associativity decides. So for (+) the :i shows infixl (i.e. left)

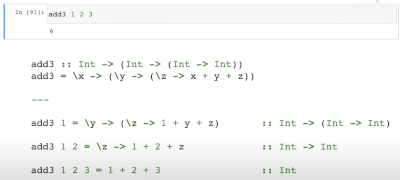

Curried Functions

All functions take on argument in Haskell. Hopefully this explains it as all functions are broken down and applied

Function application $ Operator

Gosh tired and messed with my brain but I think it means a $ will usually put parentheses around the arguments following

(2 *) 3 + 4 -- ((2 *) 3) + 4 = 10

(2 *) $ 3 + 4 -- (2 *) (3 + 4) = 14

max 5 4 + 2 -- ((max 5) 4) + 2 = 7

max 5 $ 4 + 2 -- (max 5) (4 + 2) = 6

The biggest use of $ is to replace a set of parentheses to make code more readable

show ((2**) (max 3 (2 + 2))) -- 16

show $ (2**) (max 3 (2 + 2)) -- 16

show $ (2**) $ max 3 (2 + 2) -- 16

show $ (2**) $ max 3 $ 2 + 2 -- 16

Function Composition

Here we can combine functions in one call. This just looks like chaining to me but here is the example like in Maths when you have f{g(x)} First lets look a the signature of the dot operator with my new found signature skills. The result of the second function the same type as the input to the first function and the result is the same type as the output of the first function

(.) :: (b->c) -> (a -> b) -> a -> c

f . g = \x -> f (g x)

And an example

-- IsEven function

isEven :: Int -> Bool

-- Is Odd function

isNotEven :: Bool -> String

isEven x = if x `rem` 2 == 0

then True

else False

isNotEven x = if x == True

then "This is an Even Number"

else "This is an Odd Number"

main = do

print((isNotEven.isEven) 5)

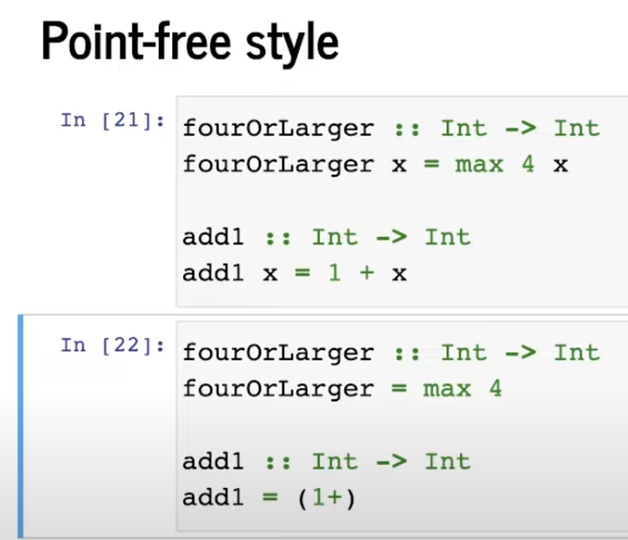

Point Free Style

Did not like the sound of this. Surely easier to decide and go with it. But here we are for reference

Recursion

Sum Example

Lets start with sum, I did not know at the beginning but (x:xs) takes a list and splits it into first element + rest

sum' :: [Int] -> Int

sum' [] = 0 -- No elements no value

sum' (x:xs) = x + sum xs

This works out as

sum'[1,2,3,4,5] = 1 + sum' [2,3,4,5]

= 1 + 2 + sum'[3,4,5]

= 1 + 2 + 3 + sum'[4,5]

= 1 + 2 + 3 + 4 + sum'[5]

= 1 + 2 + 3 + 4 + 5 + sum'[]

= 1 + 2 + 3 + 4 + 5 + 0

= 15

Where would we be without Factorial

Stone a crow

The one thing which wasn't immediately clear we that the function we do a pattern matching. I.E. if you comment of the sum' to only match on 0 then you will get the error

Non-exhaustive patterns in function sum'

Note a single quote on a function is pronounced prime. e.g. sum' = sum prime

Product Example

This points out the fact you need to think about the base case. Does not work for 0

product :: [Int] -> Int

product [] = 1 -- No elements then 1

product (x:xs) = x * sum xs

This works out as

sum[1,2,3,4,5] = 1 * product [2,3,4,5]

= 1 * 2 * product[3,4,5]

= 1 * 2 * 3 * product[4,5]

= 1 * 2 * 3 * 4 * product[5]

= 1 * 2 * 3 * 4 * 5 * product[]

= 1 * 2 * 3 * 4 * 5 * 1

= 120

Factorial Example

Where would we be without Factorial

-- Factorial

factorial :: Int -> Int

-- Base case

factorial 0 = 1

-- Recursive case

factorial n = n * factorial (n - 1)

factorial 5 = 5 * factorial[4]

= 5 * 4 * factorial[3]

= 5 * 4 * 3 * factorial[2]

= 5 * 4 * 3 * 2 * factorial[1]

= 5 * 4 * 3 * 2 * 1 * factorial[]

= 5 * 4 * 3 * 2 * 1 * 1

= 120

Steps to Create Recursion

Here is recommended steps

- Write down Type: This will help define the function

- Enumerate the possible cases based on inputs

- Between the above cases identify simplest and define

- Think about what you have available

- Define the rest

- Reflect

Drop Example

For this we drop n elements from a list. This highlight that we should consider the following cases

- We are using numbers so 0 or other

- We are using a list so empty or non-empty

A reminder of more parameters more arrows and that the last is the return value

drop' :: Int -> [a] -> [a]

-- Cases to consider

drop' : 0 [] = -- 0 and Empty list

drop' : 0 (x:xs) = 0 and Non-Empty list

drop' : n [] = non-zero and Empty list

drop' : n (x:xs) = non-zero 0 and Empty list

So we can answer 3 of the 4 cases

drop' :: Int -> [a] -> [a]

drop' : 0 [] = [] -- 0 and Empty list

drop' : 0 (x:xs) = x:xs -- what we sent is what we get back

drop' : n [] = []

drop' : n (x:xs) = drop' (n-1) xs

Improving on this and knowing we are really just pattern match we get

drop` :: Int -> [a] -> [a]

drop` : _ [] = [] -- 0 and non-zero with Empty List can be matched with _

drop` : 0 xs = xs -- confused me as xs is the rest but there are no brackets so xs is all

--Not Required drop' : n [] = []

drop` : n (_:xs) = drop' (n-1) xs -- x not used

Finally what if the pass a negative number of elements, lets assume none

drop' :: Int -> [a] -> [a]

drop' _ [] = []

drop' n xs | n <= 0 = xs -- check for negative

drop' n (_:xs) = drop' (n-1) xs

-- So now

(-3) [1,2,3] -- [1,2,3]

foldr and the Primitive Recursive Pattern

Well looking at sum and product examples above we see that there is a pattern and it is the same as the built in function foldr. This pattern is known as the ```Primitive Recursive Pattern

sum` :: [Int] -> Int

sum` foldr (+) 0

product` :: [Int] -> Int

product` foldr (*) 1

Type Classes

These are classes are assigned to types if the class is implemented for that type e.g. Bool implements Eq, Ord, Read, Show and more. This properly shows what these things are. For a type you can see the type classes it implements with :i Bool for example. Types Classes shown were

- Num

- Integral

- Fractional

- Show -- Debugging

- Read -- Reverse of show e.g. read :: [Int] "[1,2,2]" we get [1,2,3]

Non Parameterized Types

Type Synonyms

We can use Type Synonyms to make a type have a more readable but the same functionality. e.g

type Address = String

type Value = Int

type Id = String

-- Makes the function name more readable

generateTxId :: Address -> Address -> Value -> Id

generateTxId from to value = from ++ to ++ show value

New Types

We can make a new type

data Colour = Red | Green | Blue

Value Parameters

We have value parameters associated with our types

data Shape = Circle Float | Rectangle Float Float

Record Syntax

Record Syntax allows us to define our type constructors much like record in C#.

data Employee = Employee { name :: String, experienceInYears :: Float } deriving show

matt = Employee "Matt" 5

-- Update to another Matt

newMatt = matt { experienceInYears = 6.0 }

Parameterized and Recursive Types

Type Synonyms

We can also use parameterized Synonyms where we identify commonality

...

type Company = (CompanyId, Address)

type Provider = (ProviderId, Address)

-- Instead we could have

type Entity a = (a, Address)

--Examples

company = (123, ("Fred St", 999)) :: Entity CompanyId

provider = ("String", ("Fred St", 999)) :: Entity ProviderId

Parameterized Type

So we can create types with an unspecified type. We constrain it with the fat arrow (=>) for the type we are using. I guess this is like generics

--data Box a = Empty | Has a

box = Has(1:: Int)

addN:: Num a => a-> Box a -> Box a

addN _ Empty = Empty

addN n (Has a) = Has (a+n)

addN 3 Box -- Has 4

So an example

data Tweet = Tweet

{ content :: String,

likes :: Int,

comments :: [Tweet]

}

-- Example

tweet:: Tweet

tweet = Tweet "I am angry about something" 5

[ Tweet "Me too" 0 [],

Tweet "It make me angry you are angry" 2

[ Tweet "I have no ideas" 3 [] ]

]

-- Get total likes for above

engagement :: Tweet -> Int

engagement Tweet { likes = l, comments = c} = l + length c + sum(map engagement c)

engagement tweet --- 13

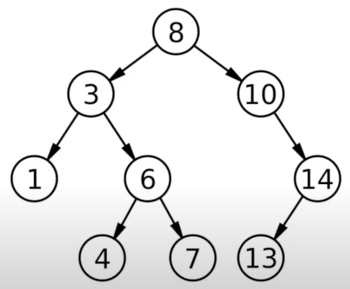

Binary Tree

Searching a binary tree seems pretty simple.

The important thing I learned was you can constrain with the fat arrow what a can be. The function has an a and a Tree of type a.

data Tree a = EmptyT | Node a (Tree a) (Tree a)

elemTree :: (Ord a) => a -> Tree a -> Bool

elemTree v EmptyT = False

elemTree v (Node x left right)

| v == x = True

| v > x = elemTree v right

| v < x = elemTree v left

Some Notes

- The type of a value constructor gives you the quantity and type of its values it takes

- The kind' of a type constructor gives you the quantity and kind of types it takes

Reading of kinds

- '*' means concrete type

- '* -> *' means type constructor takes a single concrete type and returns another concrete type

- '* -> (* -> *) -> *' means type constructor that takes one concrete type, and one single parameter type constructor and returns a concrete type

newType Keyword

Think they wanted to make it hard. This seems pretty pointless but I will wait and see. Types create with newType need to have exactly one constructor with exactly one parameter/field

newType Color a = Color a

newType Product a = Product { getProduct a}

And the answer was, it improves performance in the compiler - Sigh!!!

Creating Type Classes

To create a type class you need to

- Create a type class stating some behaviors

- Make a Type instance of that Type Class with implementation of those behaviors

Overloading

- In Haskell Overloading is multiple implementations of function or value with the same name

Example of type class

The Eq is already defined but here is how it could work. It looks like we are just defining overloaded operators like C++

-- Define class

class Eq a where

(==) :: a -> a -> Bool

(/=) :: a -> a -> Bool

-- Here is our data type

data PaymentMethod = Card | Cash | CC

-- Create instance of our PaymentMethod

Instance Eq PaymentMethod where

-- ==

Card == Card = True

Cash == Cash = True

CC == CC = True

_== _ = False

-- /=

Card /= Card = False

Cash /= Cash = False

CC /= CC = False

_== _ = True

Now this was easy but can be done better because we have repeated ourselves with the Not Equal bit. We use some called Mutual Recursion, with is when we define the negative in terms of the positive and vice-versa. Probably wont remember but the name will allow me to google it but here is the improved version

class Eq a where

(==), (/=) :: a -> a -> Bool

x /= y = not (x ==y)

x == y = not (x /=y)

-- Now we only need to define the positive as the compiler will infer the negative

Instance Eq PaymentMethod where

Card == Card = True

Cash == Cash = True

CC == CC = True

_== _ = False

-- Info for Eq class

:i Eq

type Eq :: * -> Constraint

class Eq a where

(==) :: a -> a -> Bool

(/=) :: a -> a -> Bool

{-# MINIMAL (==) | (/=) #-}

...

Because both function have the same type we can specify them in oneline. The not function which takes a boolean and returns the opposite. We can see running the info command for the Eq class we see the MINIMAL implementation is == or /=

Modules

Modules are, as ever, just functionality you can import. We looked at Data.List

main = do

print(intersperse '|' "ILoveHaskell") -- I|L|o|v|e|H|a|s|k|e|l|l

print(intercalate ' ' ["Haskell", "is", "great"]) -- "Haskell is great"

print(splitAt 3 "Apple") -- ("App","le")

And the Data.Char module.

main = do

print(toUpper 'a') -- A

print(toLower 'B' -- b

print(words 'FRED WAS') -- ["FRED", "WAS"]

And the Data.Map. The importing of this seemed to be a bit blurry even to the tutor

import Data.Map (Map)

import qualified Data.Map as Map

myMap :: Integer -> Map Integer [Integer ]

myMap n = Map.fromList (map makePair [1..n])

where makePair x = (x, [x])

main = do

print $ myMap 10

And the Data.Set

main = do

print $ Set.fromList "Hey Jude!" -- " !HJdeuy"

Roll your Own

This seem a little hairy to recompile and make sure we are running the correct code. Possibly need to look at the tools for this

module Custom(

showEven,

showOdd

) where

showEven :: Int -> String

showEven x = if x `mod` 2 == 0 then "Even" else "Odd"

showOdd :: Int -> String

showOdd x = if x `mod` 2 == 0 then "Odd" else "Even"

File IO

Reading

Very easy

main = do

contents <- readFile "movies.txt"

putStr contents

Writing

main = do

let movies = ["The Godfather", "The Shawshank Redemption", "The Dark Knight", "Pulp Fiction", "The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King"]

writeFile "movies.txt" (unlines movies)

putStrLn "Movies written to movies.txt"

Exception Handling

Here is an example of catching a division by zero in Haskell

import Control.Exception

main = do

result <- try (evaluate (div 5 0)) :: IO (Either SomeException Int)

case result of

Left ex -> putStrLn $ "Caught exception: " ++ show ex

Right val -> putStrLn $ "The result was: " ++ show val

Functors

Introduction

The definition I got from C++ is function object is a function with state.

Simple C++ Example

struct Value {

int m_result {0};

int operator()(int newResult) {

m_result = newResult;

return m_result;

}

}

int main() {

Value v;

v(42);

std::cout << v.m_result << std::endl;

}

Better C++ Example

They went on to provide a second C++ example where the Comparator was used as a good use of a functor. Calling the function Comparator with the state of the goblins.

struct Goblin {

int health;

int strength;

Goblin(int health, int strength) : health(health), strength(strength) {};

bool operator<(const Goblin& other) const {

return health < other.health;

}

};

struct GoblinComparator {

bool operator()(const Goblin& a, const Goblin& b) const {

return a.strength < b.strength;

}

};

int main() {

std::vector<Goblin> goblins {

{5, 25},

{3, 25},

{100, 1}

};

std::sort(goblins.begin(), goblins.end(), GoblinComparator());

for(const auto& goblin : goblins) {

std::cout << "Health: " << goblin.health << " Strength: " << goblin.strength << std::endl;

}

return 0;

}

// Health: 100 Strength: 1

// Health: 5 Strength: 25

// Health: 3 Strength: 25

Much Better Example

Googling to make sure I understood the idea of a functor, found a much better example. which was a logger and all makes sense now.

class Logger {

public:

Logger(const std::string& fileName) {

m_output.exceptions(m_output.badbit | m_output.failbit);

try

{

m_output.open(fileName, std::ofstream::out);

m_output << "Logger started" << std::endl;

}

catch (const std::ofstream::failure& e)

{

std::cerr << "Failure: " << e.what() << std::endl;

std::string error = "Could not open file: " + fileName;

std::cout << error << std::endl;

throw std::runtime_error(error);

}

}

void operator() (const std::string& message) {

m_output << message << std::endl;

}

public:

~Logger() {

m_output.flush();

m_output.close();

}

private:

std::ofstream m_output;

};

int main() {

Logger logger("log.txt");

logger("Hello, world!");

return 0;

}

Back to Haskell

Arggghhhhh

To I am still struggling but this is what the definition of a functor is and therefore some kind of type definition, i.e. anything which looks like this is a functor

class Functor f where

fmap :: (a->b) -> f a -> f b

The fmap definition is I guess

(a->b) -> f a -> f b

This was explained as

fmap takes a function which is of type a and results in a type b

It applies f of a and gives you a f of b

Map and FMap

So some progress, the tutor showed a couple of things which start to make more sense in the interactive session. They the types which I knew but here to keep context

:t False -- Bool

:t "hello" -- String

:t 'T' -- Char

:t 12 -- Num a=>a (an instance of typeclass Num not type)

-- Now lets look at our Maybe (like Option but instead on Some and None, Just and Nothing)

:t Nothing -- Maybe a

:t Just 5 -- Num a => Maybe a

It is the last one where thing are starting to make sense, the output suggests you put a in and you get a out. So we can now use the kind or k to look a the type constructors

:k Bool -- :: *

:k String -- :: *

:k Char -- :: *

:k Int -- :: *

-- Now lets look at our Maybe

:k Maybe -- * -> * Which means it is a function converting from type to type

So looking a map

-- Example

map (+2) [1,2,3] -- [3,4,5]

-- Looking at type

:t map -- map :: (a -> b) -> [a] -> [b]

This looks a lot like the type of fmap. fmap came first but because lists are so useful they made a specific implementation of fmap called map for lists.

You can use fmap for any shape of data but you have to tell it how to traverse the data you are using. In the example you talked about trees.

Third Video

So opening line was great, a functor is a TYPECLASS. A typeclass, you can think of as an interface you need to implement.

class Functor f where

fmap :: (a->b) -> f a -> f b

As Oliver Hardy might say, now we are getting somewhere. The video went on to distinguish between types where are wrapped and unwrapped. They eluded to the Maybe type which can be a Just or Nothing. They demonstrated unwrapped values can be evaluated

(+3) 9 -- 12 Where 9 is unwrapped

-- but

(+3) (Just 9) -- Will not work

Now the Functor for some types are already defined including, Maybe, Either and List so to demonstrate we can make our on type, a copy of Maybe using this

data Maybe2 a = Just2 a | Nothing2 deriving Show

Now we can make our own Functor for Maybe2

instance Functor Maybe2 where

fmap func (Just2 a) = Just2 (func a)

fmap func Nothing2 = Nothing2

Putting it together we have

import Data.Functor

data Maybe2 a = Just2 a | Nothing2 deriving Show

instance Functor Maybe2 where

fmap f (Just2 x) = Just2 (f x)

fmap f Nothing2 = Nothing2

main = do

print $ fmap (+1) (Just2 10) -- Just2 11

print $ fmap (+2) (Nothing2) -- Nothing2

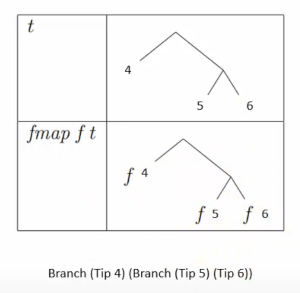

Trees

Now we come on to the tree, the most common example I have seen. For fmap and a tree we want to apply a function at the tip of the branch to get everything. This will involved recursion as a branch can have many branches

So here is a C# Recursive approach before we start

// Function to perform inorder traversal

static void inorderTraversal(Node node) {

// Base case

if (node == null)

return;

// Recur on the left subtree

inorderTraversal(node.left);

// Visit the current node

Console.Write(node.data + " ");

// Recur on the right subtree

inorderTraversal(node.right);

}

But with Haskell this does seem somewhat more readable

import Data.Functor

data Tree a = Tip a | Branch (Tree a) (Tree a) deriving Show

instance Functor Tree where

fmap f (Tip x) = Tip (f x)

fmap f (Branch left right) = Branch (fmap f left) (fmap f right)

x = Branch (Tip 4) (Branch (Tip 5) (Tip 6))

main = do

print $ fmap (*2) x

Finally

Whilst I understood functor for both C++ and Haskell, I did not understand how a C++ functor related to a Haskell one too much. Time means I march on to Monads

Applicative

Introduction

When they say applicative, they are referring to the <*> symbol. Now we use applicatives they always have a defined Functor, this has the following TypeClass definition

class Functor => Applicative f where

pure :: a-> f a

(<*> :: f (a ->b) -> f a -> f b

You will notice that the second clause is exactly the same as Functor aside from the f

Example 1

Here is an example of using the applicative

import Data.Functor

data Maybe2 a = Just2 a | Nothing2 deriving Show

instance Functor Maybe2 where

fmap f (Just2 x) = Just2 (f x)

fmap f Nothing2 = Nothing2

instance Applicative Maybe2 where

pure = Just2

Just2 f <*> Just2 x = Just2 (f x)

-- _ <*> _ = Nothing2

main = do

print $ fmap (+1) (Just2 10)

print $ fmap (+2) (Nothing2)

print $ Just2 (+3) <*> Just2 10 -- Just2 13

Example 2

Its time for the tree again

import Data.Functor

data Tree a = Tip a | Branch (Tree a) (Tree a) deriving Show

instance Functor Tree where

fmap f (Tip x) = Tip (f x)

fmap f (Branch left right) = Branch (fmap f left) (fmap f right)

instance Applicative Tree where

pure x = Tip x

Tip f <*> x = fmap f x

Branch left right <*> x = Branch (left <*> x) (right <*> x)

x = Branch (Tip 4) (Branch (Tip 5) (Tip 6))

main = do

print $ Tip (*4) <*> x -- Branch (Tip 16) (Branch (Tip 20) (Tip 24))

print $ Branch (Tip (+1)) (Tip (*2)) <*> x -- Branch (Branch (Tip 5) (Branch (Tip 6) (Tip 7))) (Branch (Tip 8) (Branch (Tip 10) (Tip 12)))

Monads

So this is the Monad bit which I what I started on to learn this. Like Functors, the explanation may have been written in greek. I have no idea what he meant

class Monad m where

return :: a -> m a

-- Bind

(>>=) :: m a -> (a -> m b) -> m b

-- Then

(>>) :: m a -> m b -> m b

x >> y = x >>= \_ -> y

-- Fail

fail :: String => m a

fail msg = error msg

He preceded to speak about 3 laws of Monads

--- Three Laws of Monads:

--- 1 Left Identity:

return a >> = f

--- the same as : f a

-- 2 Right identity:

x >>= return

-- the same as: x {Value not changed}

-- 3 Associativity:

(m >>= f) >>= g

m >>= (\x -> f x >>=g)

Moniods

The explanation was again useable. This is left here to fill in later