Python: Difference between revisions

| (3 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 1,035: | Line 1,035: | ||

</syntaxhighlight> | </syntaxhighlight> | ||

Now we can define our predicate | Now we can define our predicate functions | ||

<syntaxhighlight lang="python"> | <syntaxhighlight lang="python"> | ||

def not_below_absolute_zero(temperature): | def not_below_absolute_zero(temperature): | ||

"""Temperature not below absolute zero""" | """Temperature not below absolute zero""" | ||

return temperature._kelvin >= 0 | return temperature._kelvin >= 0 | ||

def below_absolute_hot(temperature): | |||

"""Temperature below absolute hot""" | |||

return temperature._kelvin <= 1.416785e32 | |||

</syntaxhighlight> | </syntaxhighlight> | ||

| Line 1,085: | Line 1,090: | ||

# For each property name we validate | # For each property name we validate | ||

property_names = [name for name, attr in vars(cls).items() if isinstance(attr, | property_names = [name for name, attr in vars(cls).items() if isinstance(attr, property)] | ||

for name in property_names: | for name in property_names: | ||

_wrap_property_with_invariant_checking_proxy(cls, name, predicate) | _wrap_property_with_invariant_checking_proxy(cls, name, predicate) | ||

| Line 2,107: | Line 2,112: | ||

This is because the second (top) decorator is not seen as a property. Further investigation would be need to explain why. Here is the solution | This is because the second (top) decorator is not seen as a property. Further investigation would be need to explain why. Here is the solution | ||

<syntaxhighlight lang="python"> | <syntaxhighlight lang="python"> | ||

class PropertyDataDescriptor(ABC) | from abc import ABC, abstractmethod | ||

class PropertyDataDescriptor(ABC): | |||

@abstractmethod | @abstractmethod | ||

def __get__(self,instance, owner) | def __get__(self, instance, owner): | ||

raise NotImplementedError | raise NotImplementedError | ||

@abstractmethod | @abstractmethod | ||

def __set__(self,instance, value) | def __set__(self, instance, value): | ||

raise NotImplementedError | raise NotImplementedError | ||

@abstractmethod | @abstractmethod | ||

def __delete__(self,instance) | def __delete__(self, instance): | ||

raise NotImplementedError | raise NotImplementedError | ||

@property | @property | ||

@abstractmethod | @abstractmethod | ||

def __isabstractmethod__(self,instance) | def __isabstractmethod__(self, instance): | ||

raise NotImplementedError | raise NotImplementedError | ||

# Virtual Class | # Virtual Class | ||

PropertyDataDescriptor.register(property) | |||

</syntaxhighlight> | </syntaxhighlight> | ||

Latest revision as of 04:10, 24 July 2020

Intro

Python 2 and 3 differences

print "fred" // OK Python 2

print("fred") // Not OK Python 2

Whitespace

Uses full colon and four spaces instead of brackets e.g.

for i in range(5):

x = i * 10

print(x)

Rules

- Prefer four spaces

- Never mix spaces and tabs

- Be consistent on consecutive lines

- Only deviate to improve readability

Help

help(object) gives help. e.g. for the module math

help(math)

Scalar Types, Operators, Control and Other

Types

- int (42)

- float (4.2)

- NoneType (None)

- bool ( True, False) 0 = False !=0 = True

Operators

- == value equality

- != value inequality

- < less-than

- > greater-than

- <= less-than or equal

- >= greater-than or equal

Control

if statementes

if True:

print("Its true")

h = 42

if h > 50:

print("Greater than 50")

elif h < 20:

print("Less than 20")

else:

print("Other")

while loops

while c != statement0:

print(c)

c -= 1 // c = c-1

print("Its true")

while True:

response = input()

if int(response) % 7 == 0:

break

for loops

cities = ["London", "Paris", "Berlin"]

for city in cities:

print(city)

Other

Conditional Expressions

No big surprise but

# Condition statement

if condition:

result = true_value

else:

result = false_value

# Condition expression (elvis result ? a:b

# result = true_value if condition else false_value

def sequence_class(immutable)

return tuple if immutable else list

Lambdas

Lambdas consist of the lambda keyword, argument separated by full colon and expression

lambda arg : expr

e.g.

is_odd = lambda x: x % 2 == 1

Looking a sorted the arguments are

sorted(iterable, key=None, reverse=False) --> new sorted listThe key argument must be a callable.

scientists = ['Maggie C', 'Albert E', 'Niels B']

# using a lambda, splits the names on space and this result is sorted

sorted(scientists, key=lambda name: name.split()[-1])

# Assigning shows

last_name = lamba name: name.split()[-1]

last_name

<function <lambda> at 0x103011c0

#e.g.

last_name("Fred Bloggs")

'Blogs'

# equivalent to

def first_name(name)

return name.split()[0]

Data types

Dates and Times

date

# 2014/1/6

datetime.date(2014,1,6)

datetime.date(year=2014,month=1,day=6)

# Now

datetime.date.today()

# Posix timestamp i.e. number of seconds from 1970 e.g. billionth second

datetime.date.fromtimestamp(1000000000) // datatime.data(2001,9,9)

time

datetime.time(3) // 3 hours

datetime.time(3,2) // 3 hours, 2 mins

datetime.time(3,2,1) // 3 hours, 2 mins, 1 sec

datetime.time(3,2,1,232) // 3 hours, 2 mins, 1 sec, 232 milliseconds

datetime

datetime.datetime(2003,5,12,14,33,22,245232) # 2003/05/12 14:33:22.245232

datetime.datetime.today() # Local now

datetime.datetime.now() # Local now

datetime.datetime.utcnow() # UTC now

# To combine

d = datetime.date.today()

t = datetime.time(8,15)

datatime.datetime.combine(d,t)

timedelta

These will hold the difference between two date times. e.g.

a = datetime.datetime(year=2014, month=5, day=8, hour=14, minutes=22)

b = datetime.datetime(year=2014, month=3, day=14, hour=12, minutes=9)

a-b

datetime.timedelta(55,7980)

timezones

Not sure the python people live in the real world. Default support seems poor

# Make one

cet = datetime.timezone(datetime.timedelta(hours=1), "CET")

# Make a datetime

departure = datetime.datetime(year=2014, month=1, day=7

hour=11, minute=30,

tzinfo=cet)

# Use default one

arrive = datetime.datetime(year=2014, month=1, day=7

hour=13, minute=5,

tzinfo=datatime.timezone.utc)

arrival - departure

datatime.timedelta(0,9300)

Decimal

This can be found in the decimal module and is precise to 28 places. Note the quotes in the examples as using no quotes means we are using floats - arggghhhh

Decimal('0.8') - Decimal('0.7')

# Result

Decimal('0.1')

# set this to stop usage of float constructors

decimal.getcontext().traps[decimal.FloatOperation] = True

# This will fail

Decimal0.8)

Fractions

Floating points come with problems when representing numbers such as 1/3 or other recurring values. The use of fractions provided by python may solve this.

# Two thirds

Fraction(2,3)

Complex Numbers

Python supports these by default

complex(3)

>>> (3+0j)

complex(3,2)

>>> (3+2j)

complex(3,10j)

>>> (3+10j)

Modulus in python

The standard approach to a%b = r is not how python implement this instead they use b*q + r = a. For example

In c++

#include <iostream>

int main()

{

auto a = -7;

auto b = 3;

auto c = (a) % b;

std::cout << "c = " << c << std::endl;

}

In python it uses b*q + r = a. See [[1]]

a = -7;

b = 3;

c = (a) % b;

print(c) // 2

-9 -8 -7 -6 -5 -4 -3 -2 -1 0

| | | | | | | | | |

--------------------------------------

q a

---------

rThe first number divisible by 3 is 9 if we travel negatively. The difference between this and the -7 is 2.

// Floor operator

Similar to the modulus, for integers this operates the same as the modulus and uses the next negative number going negative to calculate the answer

-9 -8 -7 -6 -5 -4 -3 -2 -1 0

| | | | | | | | | |

--------------------------------------

q a

---------

rTherefore -7 // 3 = 3. The first number divisible by 3 is -9 if we travel negatively.

str

Double and single quotes are supported. Strings are immutable. Multiline

"""This is

a multiline

string"""

m = "This string\nspans multiple\nlines"

Raw Strings like c# @

path = r'C:\users\merlin\Documents'

Format string

m = "The age of {0} is {1}".format('Jim', 32)

print(m) // The age of Jim is 32

# Or without numbers

m = "The age of {} is {}".format('Jim', 32)

# f-strings are like c#

value = 3000

m = f"The value is {value}"

bytes

These work like strings, well ascii strings as and can be created like below

b'some bytpes'

print(b[0]) // 115

decoding to bytes

norsk = "some norsk characters"

data = norsk.encode('utf8')

norwegian = data.decode('utf8')

lists

General

List are a sequence of lists

m = [1,14,5]

// Can be different types

m = ['apple', 7, false]

// Add are mutable

b = []

b.append(1.666)

b.append(1.4444)

print(b) // [1.666, 1.4444]

// Constructor

print(list("characters")) // ['c','h','a','r','a','c','t','e','r','s']

Negative indexing

You can use negative indexing - errrr

s = [3,186,4431,74400, 1048443]

print(s[-1]) // 1048443

print(s[-2]) // 74400

Slicing

Subscript of lists can be achieved with the following

s = [3,186,4431,74400, 1048443]

print(s[1:3]) // 186, 4431

print(s[1:-1]) // 186, 4431, 74400

Dict

General

Dict are value pairs

m = {'1': 'Apple', '2': 'Orange'}

print(m['1']) // Apple

# Replaces

m['1'] = 'Banana']

print(m['1']) // Banana

# Update will add if it does not exist or replace

m.update(2:'Applie')

Set

Set are values like a dictionary with no key and must be unique

k = {91,109}

k.add(54)

# Error if not found

k.remove(91)

# No Error if not found

k.discard(91)

With sets we can compare. e.g.

blue_eyes = {'Olivia','Harry', 'Lily', 'Jack','Amelia'}

blond_hair = {'Harry', 'Jack','Amelia', 'Mia','Joshua'}

# Combined

print(blue_eyes.union(blond_hair)) // {'harry','Jack','Amelia','Joshua','Mia','Olivia','Lily'}

# In both

print(blue_eyes.intersection(blond_hair)) // {'harry','Jack','Amelia'}

# Not in this

print(blond_hair.difference(blue_eyes)) // {'Mia','Joshua'}

# Not in other

print(blond_hair.symmetric_difference(blue_eyes)) // {'Mia','Joshua','Olivia','Lily'}

Tuples

Tuples look like lists but have round brackets.

t = ('Apple', 3.5, False)

# to make a single you need to use the trailing comma or it thinks it is a single type e.g.

t = ('Apple',)

# to index one with pairs use second index e.g

t = ((220,284),(220,285),(220,284),(220,281))

print(t[0][1])

Unpacking like javascript works and swapping

def minmax(items):

return min(items), max(items)

lower, upper = minmax([83, 33, 84,32, 85, 31, 86])

print(lower) // 31

print(upper) // 86

a = 'Apple'

b = 'Pear'

a, b = b, a

print(a) // Pear

print(b) // Apple

Ranges

Range supports arguments stop, start, stop or start, stop, step. e.g.

# 0-5

range(5)

# 10-20

range(10,20)

# 10-20 step 2

range(10,20,2)

Map function

Intro

This is similar to the javascript function. It creates an map object which can be iterated on a runtime. i.e. it does not produce a list only an object which next can be used on,

f = map(ord, "the quick brown fox")

a = next(f)

b = next(f)

c = next(f)

print(a) # 84

print(b) # 104

print(c) # 101

Multi Sequences

If the function needs more args you pass more args. The map ends when any of the sequences ends

sizes = ['small','medium','large']

colors = ['lavendar','teal','burnt orange']

animals = ['koala','platypus','salamander']

def combine(size,color,animal):

return '{},{},{}'.format(size,color,animal)

list(map)combine,sizes,colors, animals))

>> ['small lavender koala','medium teal platypus','large burnt orange salamander']

Filter function

Intro

This accepts a function and a single sequence and like map returns an object not a result. Only the elements which return True are returned.

myObject = filter(is_odd, [1,2,3,4,5,6,7])

None

You can pass None as the function and only the true objects are returned

myObject = filter(None, [0,1, False,True, [], [1,2,3],'','hello'])

>> [1, True, [1,2,3],'hello'])

Reduce

Repeatedly apply a function to the elements of a sequence reducing them to a single value

reduce(operator.add, [1,2,3,4,5])

>>15

# With start value

reduce(operator.add, [1,2,3,4,5],100)

>>115

Comprehensions

List Comprehension Syntax

Generally this is

[expr(item) for item in iterable]

words = "Why sometimes I have believed"

print([len(word) for word in words]) // [3,9, 1, 4, 8]

These can be more complex. e.g.

[(x,y) for x in range(5) for y in range(3)]

[(0,0),(0,1),(0,2),(1,0),(1,1),(1,2),(2,0),(2,1),(2,2),(3,0),(3,1),(3,2),(4,0),(4,1),(4,2)]

# Which is the same as

point = []

for x in range(5)

for y in range(3)

points.append((x,y))

points

Dict Comprehensions

Like lists above

{expr(key:) expr(value) for item in iterable}

country_to_capital = { 'UK': 'London',

'Brazil': 'Brasilia',

'Sweden': 'Stockholm' }

capital_to_country = { capital: country for country, capital in country_to_capital.items()}

print(capital_to_country) // {'Brasilia': Brazil, 'London': 'UK', 'Stockholm': 'Sweden'}

Iteration

Iterators

Here is how to iterate

s = [1,2,3,4]

myIterator = iter(s)

item1 = next(myIterator)

print(item1) // 1

item2 = next(myIterator)

print(item2) // 2

Writing Own Iterator

Just implement __iter__ and __next__

class ExmapleIterator

def __init__(self,data):

self.index = 0

self.data = data

def __iter__(self):

return self

def __next__(self):

if self.index >= len(self.data):

raise StopIteration()

rslt = self.data[self.index]

self.index += 1

return rslt

Using second argument of iter

The second argument of iter allows you to test the result and exit if True. e.g.

# You should

# see this

# text.

# END

# But not

# this text.

with open('the_above_text.txt', 'rt') as f:

for line in iter(lambda: f.readline().strip(), 'END');

>> You should

>> see this

>> text.

Generators

Generator functions

This is just like javascript redux stuff

def gen123():

yield 1

yield 5

yield 3

myIterator = gen123()

print(next(myIterator)) // 1

print(next(myIterator)) // 5

print(next(myIterator)) // 3

print(next(myIterator)) // Exception

# Or

for v in gen123():

print(v)

...

1

5

3

Generator Expressions

Syntax can be defined as

(expr(item) for item : iterable)

million_squares = (x*x for x in range(1,1000001))

# Generate and output last 10

list(million_squares)[-10:]

# Again will yield nothing

list(million_squares)

Iteration tools

islice

from itertools import count, islice

thousand_primes = islice( (x for x in count() if is_prime(x), 1000)

# thousand_primes is a special islice object which is iterable

# converting to a list

list(thousand_primes)[-10:]

[7841,7853, ..... 7919]

# so to sum first thousand primes

sum(islice( (x for x in count() if is_prime(x), 1000))

3682913

zip

Combine groups together e.g.

sunday = [10,20,30]

monday = [101,201,301]

for item in zip(sunday, monday)

print(item)

...

(10,101)

(20,201)

(30,301)

Exceptions and Errors

Intro

There are many exceptions predefined in python. Checkout the exception hierarchy on the docs page [[2]]. Don't forget about mro() to investigate them.

General

def convert(s):

try:

number = ''

for token in s:

number += DIGIT_MAP[token]

x = int(number)

# Can be on one line

# except (KeyError, TypeError):

except TypeError:

x = -2

raise # rethrow

except KeyError:

x = -1

raise # rethrow

return x

Chaining

Implicit

It an exception occurs as a consequence of an exception the original is stored in __context__

def main():

try:

a = triangle(3,4,10)

print(a)

except TriangleError as e:

try:

print(e, file=sys.stdin) # Deliberate error

except io.UnsupportedOperation as f:

print(e)

print(f)

print(f.__context__ is e)

Explicit

We can catch a known exception and wrap it in our application exception. __cause__ will contain the original exception.

def main():

try:

return math.degrees(math.atan(5,0))

except ZeroDivisionError as e:

raise MyOwnError from e:

print(e)

print(e.__cause__)

Traceback

StackTrace information is available via the __trackback__ and can be printed easily.

def main():

try:

return math.degrees(math.atan(5,0))

except ZeroDivisionError as e:

raise MyOwnError from e:

print(e.__trackback__)

trackback.print_tb(e.__trackback__)

s = trackback.format_tb(e.__trackback__)

print(s)

Asserts

Internal Invariants

You can add assertions in the code to confirm it is working as expected. It only operates if the assertion is true

def modulus_three(n):

r = n % 3

if r == 0:

print("Multiple of 3")

elif r == 1

print("Remainder 1")

else:

assert r == 2, "Remainder is not 2"

print("Remainder 2")

Class Invariants

You can add class assertions on methods. Note unless you run the code with the -O options these are executed and can of course cause performance issues

class SortedClass:

...

def count(self)

assert self._is_unique_and_sorted()

# Must be sorted to work

return int(item in self)

...

def _is_unique_and_sorted(self):

return all(self[i[ < self[i+1] for i in range(len(self) -1))

Context Managers

Intro

For C# this would be the using statement or the dispose pattern. For C++ this is the constructor and destructor. The python course explained it as and uses __enter__() and __exit__()

with context-manger:

context-manager.begin()

body

context-manager.end()

If the __exit__() returns False, the default, the exception is propagated.

Examples

Without contextlib

class LoggingContextManager:

def __enter__(self):

print('logging_context_manager: enter')

return self

def __exit__(self, exc_type, exc_val, exc_tb):

if(exc_type is None:

print('logging_context_manager: normal exit)

else:

print('logging_context_manager: exception '

'type={}, value={}, traceback={}'.format(

exc_type, exc_val, exc_tb))

With contextlib using generator function

import contextlib

import sys

#contextlib.contextmanager

def logging_context_manager():

print('logging_context_manager: enter')

try:

yield 'You are in a with-block!'

print('logging_context_manager: normal exit)

except Exception:

print('logging_context_manager: exception exit',

sys.exc_info())

Functions

General Functions

These are created as below

def foo(arg1, arg2):

return arg1 * arg2

Default Arguments

def foo(arg1, arg2=9):

return arg1 * arg2

Be aware that the def assignment is only run once. Therefore These are created as below

def add_spam(menu=[]):

menu.append('spam')

add_spam() // ['spam']

add_spam() // ['spam','spam']

Advice is to make default arguments not mutable. i.e. not strings and not ints

def add_spam(menu=None):

if(menu==None)

menu = []

menu.append('spam')

return menu

add_spam() // ['spam']

add_spam() // ['spam']

Extended Formal Arguments (params)

Intro

Remember we have positional and keyword arguments in python

Positional arguments

def with an argument prefixed with an asterix means the arguments being passed are a tuple. e.g.

def test(*arg):

print(args)

print(type(args))

test(1,2,3)

1,2,3

<class tuple)

Keyword arguments

def with an argument prefixed with two asterix means the arguments being passed are a dict. e.g.

def test(name, **kwargs):

print(name)

print(kwargs)

print(type(kwargs))

test('img', src="monet.jpg", alt="Sunrise by Claude", border=1)

img

{'src':'monet.jpg', 'border':'1', 'alt':'Sunrise by Claude'}

<class dict)

Extended Call Syntax

Equally the calling of functions can use keyword two asterix. Doing so means the positional parameters are satisfied and the remaining parameters are used to make keyword arguments. e.g.

def color(red, green, blue, **kwargs):

print("r =", red)

print("g =", green)

print("b =", blue)

print(kwargs)

k = {'red': 21,'green': 22,'blue': 23,'alpha': 24, 'beta': 25}

color(**k)

r = 21

g = 22

b = 23

{'alpha' :24, 'beta': 25}

Returning Functions

Intro

In python you can return a function and execute it.

def enclosing():

def local_function():

print('Hi')

return local_function

lf = enclosing()

lf() # // Hi

Factories

We can combine the values are creation of the function with the arguments of the execution of the function. Look at variable exp which is created on execution of raise_to e.g.

def raise_to(exp):

def raise_to_exp(x):

return pow(x,exp)

return raise_to_exp

myfoo = raise_to(2)

myfoo(10) # // 100

myfoo(5) # // 25

Decorators

Intro

Like c# the functions can be decorated. e.g.

from functools import wraps

def check_non_negative(f):

@wraps(f)

def inner_check_non_negative(*args, **kwargs):

print("Got here didn't I")

for value in args:

if value < 0:

raise ValueError(

"Value {} must be greater than 0".format(value))

return f(*args, **kwargs)

return inner_check_non_negative

@check_non_negative

def create_list(value, size):

print("And here")

return [value] * size

create_list(10, -10)

The functools.wrap is necessary to help the support tools such as help.

With parameters

Like typescript you can pass arguments to your decorator by wrapping a decorator in a function and returning the decorator. e.g.

from functools import wraps

def check_non_negative(arg1):

def wrap(f):

print("Inside wrap()")

@wraps(f)

def wrapped_f(*args):

for value in args:

if value < arg1:

raise ValueError(

"Value {} must be greater than {}".format(value, arg1))

f(*args)

return wrapped_f

return wrap

@check_non_negative(10)

def create_list(value, size):

print("And here")

return [value] * size

create_list(10, 10)

create_list(10, -10)

The functools.wraps is necessary to help the support tools such as help.

Class Decorator

Instances

Instances of Classes can be used as Decorators provide they implement the __call__ method

Non Instances

Intro

Here is an example of a simple class decorator. The decorator function accepts only one argument cls.

def my_class_decorator(cls)

for name, attr in vars(cls).items():

print(name)

return cls

@my_class_decorator

class Temperature:

def __init__(self, kelvin)

self._kelvin = kelvin

# Not very python getters and setters

def get_kelvin(self)

return self._kelvin

def set_kelvin(self,value)

self._kelvin = value

# This produces

from class_decorators import *

__module__

get_kelvin

set_kelvin

__init__

__weakref__

__dict__

Detail

Wrapping the functions

This is very much related to the metaclasses section and was quite involved.

First we created a class which was able to check the functions each time the class was used. Like Typescript we create a factory wrapper for the decorator

def invariant(predicate):

def invariant_checking_class_decorator(cls):

# For each method name we validate

method_names = [name for name, attr in vars(

cls).items() if callable(attr)]

for name in method_names:

_wrap_method_with_invariant_checking_proxy(cls, name, predicate)

return cls

return invariant_checking_class_decorator

The proxy method looks like this

from functools import wraps

def _wrap_method_with_invariant_checking_proxy(cls, name, predicate):

method = getattr(cls, name)

assert callable(method)

@wraps(method)

def invariant_checking_method_decorator(self, *args, **kwargs):

result = method(self, *args, *kwargs)

if not predicate(self):

raise RuntimeError(

"Class invariant {!r} violated for {!r}".format(predicate.__doc__, self))

return result

setattr(cls, name, invariant_checking_method_decorator)

Now we can define our predicate functions

def not_below_absolute_zero(temperature):

"""Temperature not below absolute zero"""

return temperature._kelvin >= 0

def below_absolute_hot(temperature):

"""Temperature below absolute hot"""

return temperature._kelvin <= 1.416785e32

Finally the new decorator can be used. Phewww!

@invariant(not_below_absolute_zero)

class Temperature:

def __init__(self, kelvin):

self._kelvin = kelvin

# Not very python getters and setters

def get_kelvin(self):

return self._kelvin

def set_kelvin(self,value):

self._kelvin = value

Wrapping the properties

This approach works until you introduce properties which are not functions.

Adding the properties to the temperature class

class Temperature

...

@property

def celsius(self):

return self._kelvin - 273.15

@setter.celsius

def celsius(self,value):

self._kelvin = value + 273.15

...

Shows that this no longer works. This is because properties are not functions so we have to add checking of properties to the invariant function

def invariant(predicate):

def invariant_checking_class_decorator(cls):

# For each method name we validate

method_names = [name for name, attr in vars(cls).items() if callable(attr)]

for name in method_names:

_wrap_method_with_invariant_checking_proxy(cls, name, predicate)

# For each property name we validate

property_names = [name for name, attr in vars(cls).items() if isinstance(attr, property)]

for name in property_names:

_wrap_property_with_invariant_checking_proxy(cls, name, predicate)

return cls

return invariant_checking_class_decorator

And we need to define the proxy for the properties invariant checker

def _wrap_property_with_invariant_checking_proxy(cls, name, predicate)

prop = getattr(cls, name)

assert isinstanceof(prop,property)

invariant_checking_proxy = InvariantCheckingPropertyProxy(prop, predicate)

setattr(cls, name, invariant_checking_proxy)

Finally we can write our proxy

class InvariantCheckingPropertyProxy:

def __init__(self, referent, predicate):

self._referent = referent

self._predicate = predicate

def __get__(self,instance,owner):

if instance is None:

return self._referent

result = self._referent.__get__(instance,owner)

if not self._predicate(instance):

raise RuntimeError("Class invariant {!r} violated for {!r}".format(self._predicate.__doc__,instance))

return result

def __set__(self,instance,value):

result = self._referent.__set__(instance,value)

if not self._predicate(instance):

raise RuntimeError("Class invariant {!r} violated for {!r}".format(self._predicate.__doc__,instance))

return result

def __delete__(self,instance):

result = self._referent.__delete__(instance)

if not self._predicate(instance):

raise RuntimeError("Class invariant {!r} violated for {!r}".format(self._predicate.__doc__,instance))

return result

Multiple Decorator

Decorators can be multiple. They are executed in reverse order. i.e. decorator1, decorator2

@decorator1

@decorator2

def northern_city()

return ;'Troms0'

Modularity

Importing defs

Best to be selective

from words import (fetch_words, print_words)

// could be BAD BAD!!

from words import *

Passing arguments

import sys

if __name__ == '__main__':

main(sys.argv[1])

Comments

def fetch_words(url):

"""Fetch a list of words from a URL.

Args:

url: The URL of UTF-8 text document.

Return:

A list of strings containing the words from

the document.

"""

story = urlopen(url)

story_words = []

for line in story:

line_words = line.decode('utf8').split()

for word in line_words:

story_words.append(word)

story.close()

return story_words

Scope of Objects

Types of Scope

- Local - Inside current function

- Enclosing - Inside enclosing function

- Global - At the top level of the module

- Built-in - In the special builtins module

Overriding Scope

global

Not using global creates a new count and it shadows the global count.

count = 0

def show_count():

print(count)

def set_count(c)

global count = c

set_count(5)

show_count()

nonlocal

Where there are functions within functions the nonlocal keyword may be used. e.g.

count = 0

def enclosing():

count = 5

def local():

nonlocal count

count = 25

Objects and Types

Named references to objects

Assigning variables is the same as references. Use id() to prove this.

s = [1,2,3]

r = s

s[0] = 500

print(r)

[500,2,3]

p = [4,5,6]

q = [4,5,6]

print(p == q) // True

print(p is q) // False

Passing Arguments are like references

Passing arguments is like passing references

m = [9,15,24]

def modify(k):

k.append(39)

print("k = ", k)

modify(m)

k = [9,15,24, 39]

print(m)

[9,15,24, 39]

Passing Arguments are like references II

Or are they. g is reassigned not mutated

f = [14, 23, 37]

def replace(g):

g = [17,28, 45]

print("g = ", g)

replace(f)

g = [17,28, 45]

print(f)

[14,23,37]

Classes

General

class Fight:

def __init__(self, registration, model, num_rows)

self._registration = registration

self._model = model

self._num_rows = num_rows

def registration(self):

return self._registration

def model(self):

return self._model

def num_rows(self):

return self._num_rows

Access

There is no public, protected or private in Python

Inheritance

Intro

This is achieved using brackets on the name

class MyBaseClass:

def registration(self):

return self._registration

def model(self):

return self._model

def num_rows(self):

return self._num_rows

class Fight(MyBaseClass):

def __init__(self, registration, model, num_rows)

self._registration = registration

self._model = model

self._num_rows = num_rows

Multiple Inheritance

Python supports this. For initializers, only the first base class is automatically called. Where there are methods are defined the same the MRO or Method Resolution Order is used. This can be seen with classname.__mro__. This can also be obtained by calling classname.mro(). In general the class is search in declaration order.

class Fight(MyBaseClass1,MyBaseClass2,MyBaseClass3):

def __init__(self, registration, model, num_rows)

self._registration = registration

self._model = model

self._num_rows = num_rows

super

Super is not like a keyword but instead a function with arguments in Python. There are rules about what it returns based on those arguments.

Class-bound proxy

This is a class bound proxy

super(base-class), derived-class)

Where base-class is a class object and derived-class is a subclass of first argument

- Python finds MRO for derived-class

- It then finds base-class in that MRO

- It takes everything after base-class in the MRO and finds the first class in the sequence with a matching method name

Instance-bound proxy

This is a instance bound proxy

super(class), instance-of-class)

Where class is a class object and instance-of-class is a instance of the first argument

- Python finds MRO for the type of the second argument

- It then finds the location of the first argument in that MRO

- It takes everything after that for matching method name

Super no arguments

You can call super with no arguments. It populates the parameters depending on instance or class method

Instance

super(class-of-method, self)

Class

super(class-of-method, class)

Base Class Init

This is not called by default. To call the base class call super. e.g.

class RefridgeratedShippingContainer(ShippingContainer):

MAX_CELSIUS = 4.0

def __init__(self, owner, contents, celsius):

super().__init__(owner, contents)

Factories for Derived Classes

Using extended call arguments we can work around creating derived classes using base class. e.g.

class BaseClass:

def create_default(cls, attr1):

return cls(attr1, *args, **kwargs)

def __init__(self, attr1):

self._attr1 = attr1

class DervivedClass(BaseClass):

def __init__(self, attr1, attr2):

self._attr1 = attr1

self._attr2 = attr2

f = DervivedClass.create_default('A1','A2')

Static methods

Note if you are calling static methods on classes you should use self and not the class name as this will provide polymorphic behavior unless you do not want this :)

String and Representations

Bit of python up themselves here. Basically repr is for developers and explicit where str is for clients.

class Point2D

def __init__(self,x,y):

self.x = x

self.y = y

def __str__(self):

return '({}, {})'.format(self.x, self.y)

def __repr__(self):

return 'Point2d(x={}, y={})'.format(self.x, self.y)

Properties

Getters and Settters

Not great but this appears to be like this

class MyClass:

# Getter

@property

def myattribute(self)

return self._myattribute

# Setter

@myattribute.setter

def myattribute(self,value)

self._myattribute = value

Derived Class Getters and Settters

In derived class the the getter can be overridden by just redefining. Setter requires you to reference the class which contains the property. e.g.

class MyClass:

# Getter

@property

def myattribute(self)

return self._myattribute

# Setter

@myattribute.setter

def myattribute(self,value)

self._myattribute = value

class Derived(MyClass):

# Setter

@MyClass.myattribute.setter

def myattribute(self,value)

if(value > 10):

raise ValueError("Value out of range")

self._myattribute = value

Horrible access to base class setter

You can access this be calling the baseclassname.attribute.fset(self,value). Which is horrible like this.

class MyClass:

# Getter

@property

def myattribute(self)

return self._myattribute

# Setter

@myattribute.setter

def myattribute(self,value)

self._myattribute = value

class Derived(MyClass):

# Setter

@MyClass.myattribute.setter

def myattribute(self,value)

if(value > 10):

raise ValueError("Value out of range")

MyClass.myattribute.fset(self,value)

__call__

No idea why this is good but essentially it allows to call an instance of an object with no method or rather the method name __call__

class Test

def __init__(self)

self._cache = {}

def __call__(self, arg1)

if arg1 not in self._cache:

self._cache[arg1] = socket.gethostbyname(arg1)

return self_cache[host]

f = Test()

f('bibble.co.nz')

Static Attributes

You qualify the attribute with the class name

class Test:

a_static = 112

def __init__(self, registration, model, num_rows)

self._registration = registration

self._model = model

self._num_rows = num_rows

Test.a_static = Test.a_static + 1

Static Method

Intro

These seem very similar. The tutorial said the rule is simple if you need to refer to the class object within the method, e.g. a class attribute, use class method.

@staticmethod

No access needed to either class or instance objects.

class Test:

a_static = 1337

@staticmethod

def _get_next_serial():

result = Test.a_static

Test.a_static = += 1

return result

def __init__(self, registration, model, num_rows)

self._registration = registration

self._model = model

self._num_rows = num_rows

Test.a_static = Test._get_next_serial()

@classmethod

Requires access to the class object to call other class methods or the constructor

class Test:

a_static = 1337

@classmethod

def _get_next_serial(cls):

result = cls.a_static

cls.a_static = += 1

return result

def __init__(self, registration, model, num_rows)

self._registration = registration

self._model = model

self._num_rows = num_rows

self.a_static = Test._get_next_serial()

A typical use may be a factory. e.g.

class Test:

a_static = 1337

@classmethod

def create_empty_test(cls):

return cls("","", 0)

@classmethod

def create_default_test(cls):

return cls("XXX","YYY", 1)

def __init__(self, registration, model, num_rows)

self._registration = registration

self._model = model

self._num_rows = num_rows

self.a_static = Test._get_next_serial()

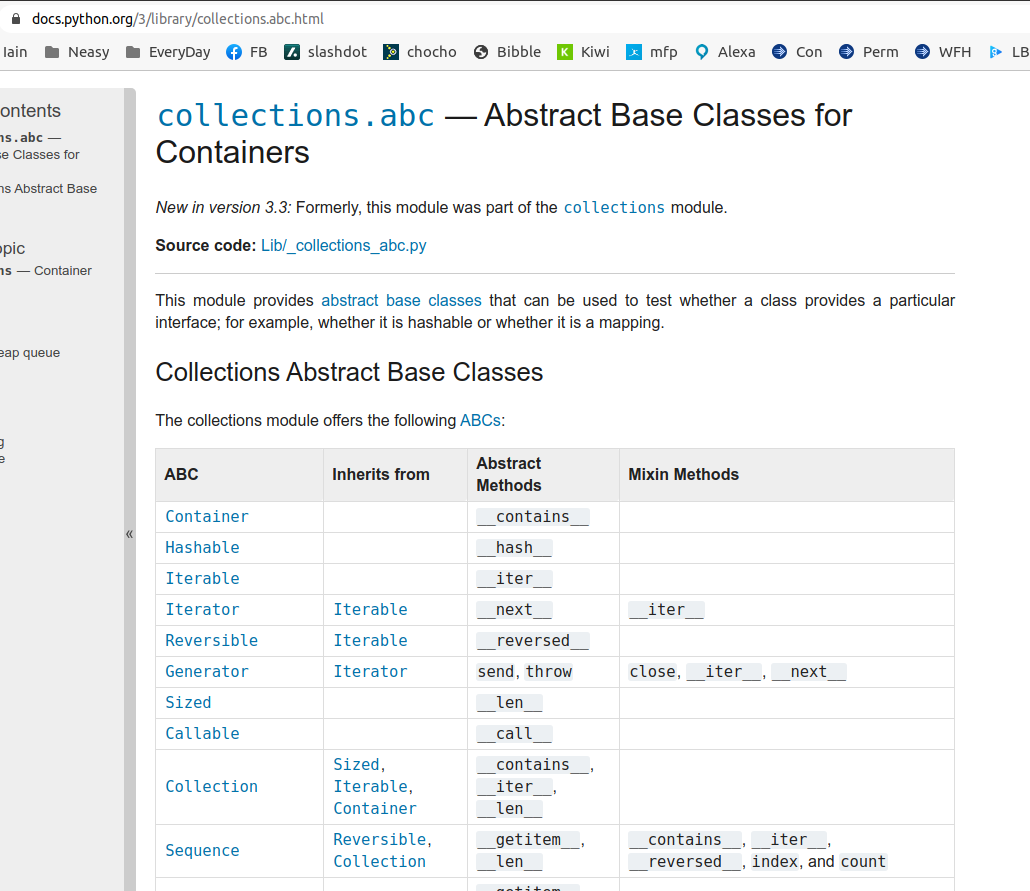

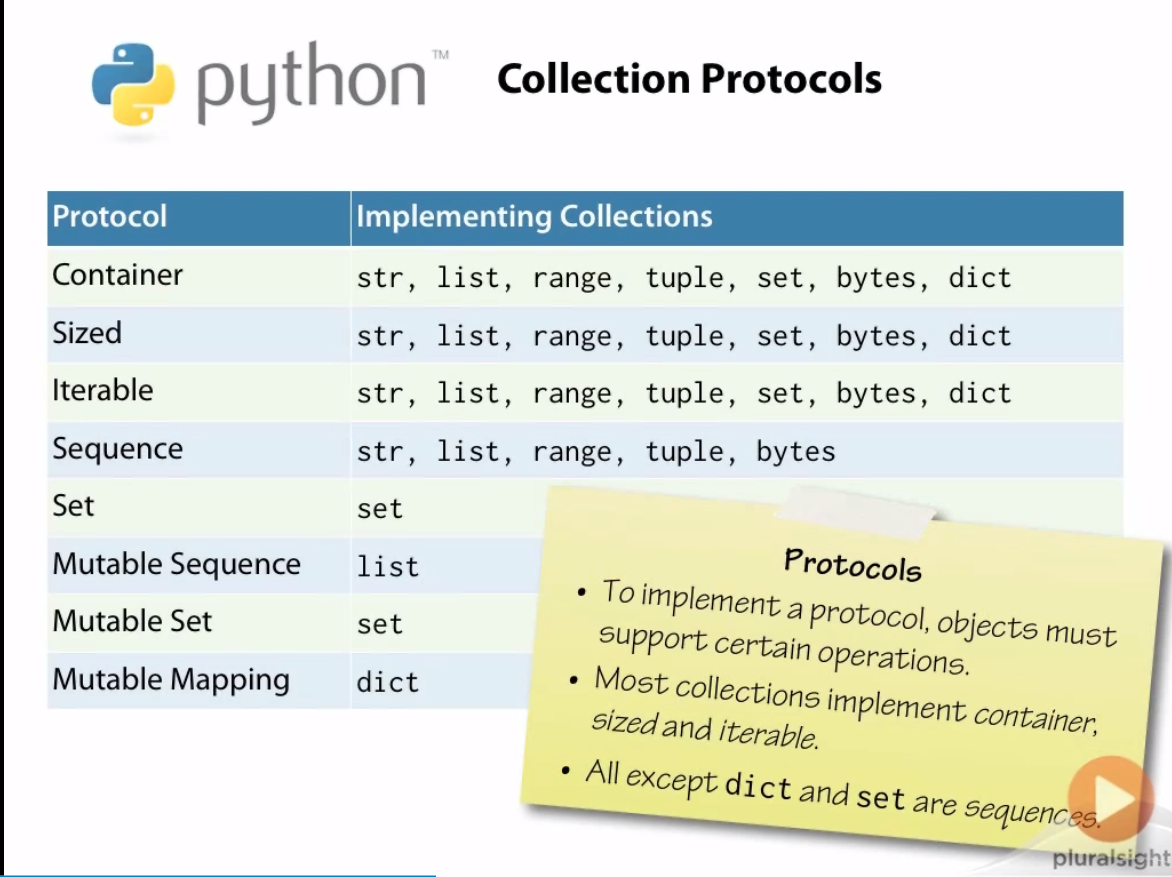

Collections

Intro

Python has the following collection protocols.

Intro

Create a collection which is a sorted set

class SortedSet:

def __init__(self, items=None)

self._items = sorted(items)Container Protocol

This supports the in and not in tests and implements the special method __contains__(item)

class SortedSet:

def __init__(self, items=None)

self._items = sorted(items) if items is not None else []

def __contains__(self, item)

return item in self._itemsSized Protocol

This supports the len(sized) function and must not modify the colection and implements the special method __len__()

class SortedSet:

def __init__(self, items=None)

self._items = sorted(set(items)) if items is not None else []

def __contains__(self, item)

return item in self._items

def __len__(self)

return len(self._items)Iterable Protocol

This supports the iter(iterable) function and implements the special method __iter__()

class SortedSet:

def __init__(self, items=None)

self._items = sorted(set(items)) if items is not None else []

def __contains__(self, item)

return item in self._items

def __len__(self)

return len(self._items)

def __iter__(self)

return iter(self._items)

# alternative to above

def __iter__(self)

for item in self._items:

yield itemSequence Protocol

Introduction

Lots to do

- Retrieve slices by slicing item = seq[index], seq[start:stop]

- Produce a reversed sequence r = reversed(seq)

- Find items by value index = seq.index(item)

- Count items num = seq.count(item)

- Concatenate with + operator

- Repetition with * operator

- Implement method __mul__() and __rmul__()

The abstract base class or abc provides a sequence class which implements most of the sequence functionality for us

First Bash

So the code

from collections.abc import Sequence

class SortedSet(Sequence):File:Binary search.png

def __init__(self, items=None)

self._items = sorted(set(items)) if items is not None else []

def __contains__(self, item)

return item in self._items

def __len__(self)

return len(self._items)

def __iter__(self)

return iter(self._items)

def __getitem__(self, index)

result = self.items[index]

# Check for slice as argument and if so sort

return SortedSet(result) if isinstance(index, slice) else result

def __repr__(self)

return "SortedSet({})".format(

repr(self.items) if self._items else ''

)

def __eq__(self,rhs)

# check expected type

if not isinstance(rhs,SortedSet)

return NotImplemented

return self._items == rhs._items

def __ne__(self,rhs)

# check expected type

if not isinstance(rhs,SortedSet)

return NotImplemented

return self._items != rhs._itemsPerformance of Count

Count in the original solution uses the count method from sequence and there is an O(n). Given there can be only one occurrence it makes sense to use a binary search

def count(self, item):

# Do a binary search from the left

index = bisect_left(self._items, item)

# (index != len(self._items)) Check if in the bound of the collection

# self._items[index] == item Check if the item is the one we are looking for

found = (index != len(self._items)) and (self._items[index] == item)

return int(found)Looking at the code for count we notice that the first 2 lines are just detecting if the value is contained in the set and therefore, now efficient, can be moved to __contains__

def __contains__(self, item):

index = bisect_left(self._items, item)

return (index != len(self._items)) and (self._items[index] == item)

def count(self, item):

return int(item in self)Performance of Index

Using what we knew from count

def index(self, item):

# Do a binary search from the left

index = bisect_left(self._items, item)

if (index != len(self._items)) and (self._items[index] == item):

return index

raise ValueError("{} not found".format(repr(item)))Concatenation and Repetition

To implement this we use the chain function from itertools. Using this reduces the use of temporaries

def __add__(self, rhs):

return SortedSet(chain(self._items, rhs._items))For repetition

def __mul__(self, rhs):

return self if rhs > 0 else SortedSet()

def __rmul__(self, lhs):

return self * lhsNow we can remove the Sequence class as we now implement the necessary functions.

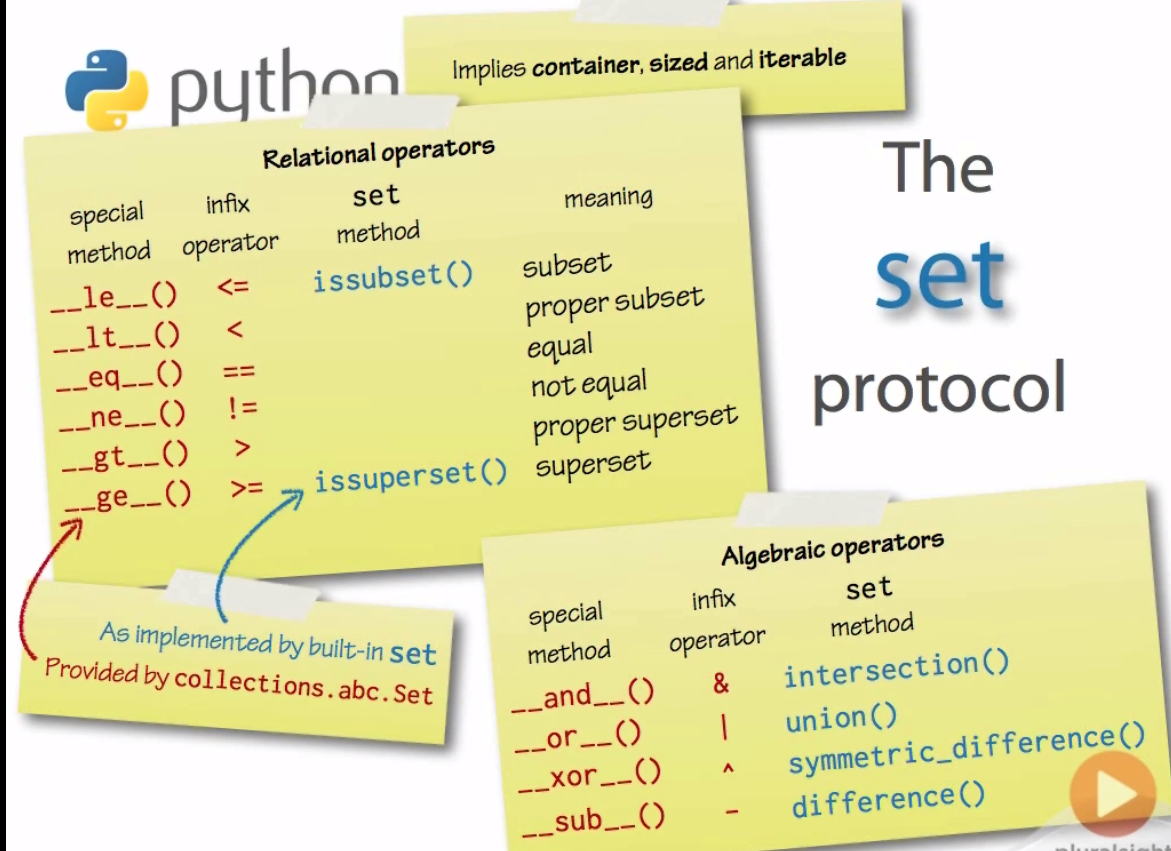

Set Protocol

Set requires us to look at the Relationship and Algebraic operators.

Introduction

# Is a subset of e.g. A [1,2,3] is a subset of [1,2,3,4,5]

def isssubset(self, iterable):

return self <= SortedSef(iterable)

# Is a super set of e.g. A [1,2,3,4,5] is a super set of [1,2,3]

def isssuperset(self, iterable):

return self >= SortedSef(iterable)

# Is an intersection e.g. s [1,2,3], t [2,3,4] gives [2,3]

def intersection(self, iterable)

return self & SortedSet(iterable)

# Is an union e.g. s [1,2,3], t [2,3,4] gives [1,2,3,4]

def union(self, iterable)

return self | SortedSet(iterable)

# Xor items not in both sets

def symmetric_difference(self, iterable)

return self ^ SortedSet(iterable)

# Items in lhs but not in rhs

def difference(self, iterable)

return self - SortedSet(iterable)Advanced Python

Flow Control

While else

This in not liked but is available in python

while condition: execute_when_true() else: # nobreak execute_when_false()

For else

Same a While else but for for loops

for item in iterable

if match(item):

result = item

break

else: # nobreak

result = None

# Always come here

print(result)Try else

More of the same

try:

f = open(filename,'r')

except OSError:

print('File could not be open')

else:

print('Number of lines', sum(1 for line in f))

f.close()Switch or Case

There is no switch or case in python. One approach is to implement a dictionary with a function to execute. Another approach is to use singledispatch where you define types you support.

@singledispatch

def draw(shape):

raise TypeError("Dont know how".format(shape))

@singledispatch(Circle)

def _(shape):

print("\u25CF" if shape.solid else "\u25A1")

@singledispatch(Parallelogram)

def _(shape):

print("\u25B0" if shape.solid else "\u25B1")

@singledispatch(Triangle)

def _(shape):

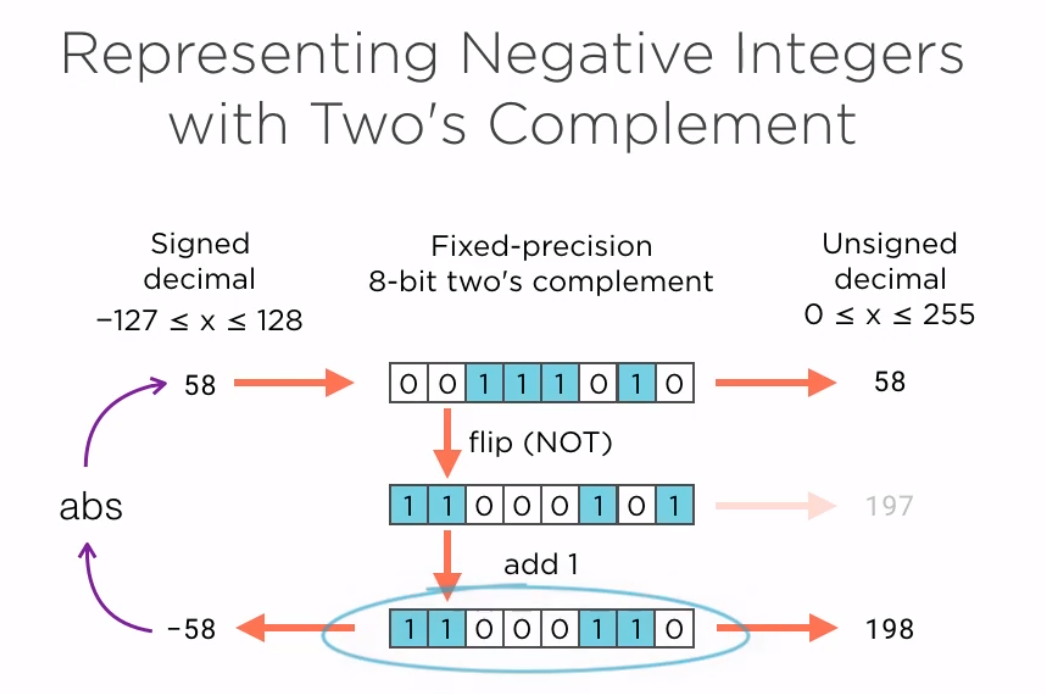

print("\u25B2" if shape.solid else "\u25B3")Byte-Orientated Programming

Intro

- & And Operator

- | Or Operator

- ^ XOR Exclusive-Or Operator 11100100 ^ 00100111 = 11000011

- ~ Not Compliment Operator 00000000 ~ 11110000 = -11110001

- << Left Shift

- >> Right Shift

Two Compliment

This is how twos compliment works

byte Type and bytearray

Byte Type is immutable and bytearray IS mutable

bytes()

>>> b''

bytes(5)

>>> b'\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00'

bytes(range(65, 65+26))

>>> b'ABCDEFGHIJKMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ'

# Convert from non ascii text not pictured here

bytes('Some foreign chars', 'utf16')

>>> b'\xff\xfeN\x00r\x00w'

# Convert from Hex

bytes.fromhex('54686520')

>>> b'The 'Example Program for reading c structures in Python

This shows the use of memoryview, mmap and struct.iter_unpack. This can be found here Python Bytes Reading Example

Object Internals

Looking at the course it described

- __dict__ dictionary containing attributes

- __getattr__ override get attribute

- __setattr__ override set attribute

- __delattr__ override delete attribute

- __getattribute__ overrides all attributes, __getattr__ is the fallback

Nice to know but would need a reason to investigate further. I am guessing creating objects on the fly would be the reason.

You can also override __new__ the function called on creation of a class. This can save memory by implementing object interning. This is really for a rainy day

Slots

To reduce the system of objects but disallow additional attributes you can use slots e.g.

class Test:

__slots__ = ['attr1','attr2','attr3']

def __init__(self, attr1,attr2,attr3):

self.attr1 = attr1

self.attr2 = attr2

self.attr3 = attr3

import sys

test = Test(1,2,3)

sys.getsizeof(test)This is not recommended but can resolve issues sometimes.

Descriptors

Python provides a descriptor protocol. This can help in the simplification of properties code. Below is the @property approach example

class Planet

def __init__(self,

radius_meters,

mass_kilos):

self.radius_meters = radius_meters

self.mass_kilos = mass_kilos

@property

def radius_meters(self)

return self._radius_meters

@radius_meters_setter

def radius_meters(self,value)

if value <= 0

raise ValueError('radius_meters value {} is not positive.'.format(value)

self._radius_meters = value

@property

def mass_kilos(self)

return self._mass_kilos

@mass_kilos_setter

def mass_kilos(self,value)

if value <= 0

raise ValueError('mass_kilograms value {} is not positive.'.format(value)

self._mass_kilos = valueThe Python descriptor protocol expects you to define

- __get__

- __set__

- __delete__

Below is an implementation of a descriptor which only allows positive entries

from weakref import WeakKeyDictionary

class Positive:

def __init__(self):

self._instance_data = WeakKeyDictionary()

def __get__(self, instance, owner):

return self._instance_data[instance]

def __set__(self, instance, value):

if value <= 0:

raise ValueError)"Value {} is not postivie".format(value))

self._instance_data[instance] = value

def __delete__(self, instance):

raise AttributeError("Cannot delete attribute")

Applying this to the Planet class gives the following

class Planet

def __init__(self,

radius_meters,

mass_kilos):

self.radius_meters = radius_meters

self.mass_kilos = mass_kilos

radius_meters = Positive()

mass_kilos = Positive()MetaClasses

Intro

With python you can change the behaviour of the underlying metaclasses. This is done by defining classes derived from the class type.

Example

A example is shown below which prevents the reusing of the method name.

class Dodgy()

def wouldnt_happend_in_cpp(self):

return "first method"

def wouldnt_happend_in_cpp(self):

return "second method"Here we create a metaclass

First create a dictionary which does not allow addition value for existing key.

class OnShotClassNamespace(dict)

def __init__(self,name, existing=None)

super.__init()

# We capture name to make message nicer

self._name = name

if existing is not None:

for k, v in existing:

self[k] = v

def __setitem__(self, key, value)

if key in self:

raise ValueError("Cannot assign to existing key {!r}".format(key))

super.__setitem(key,value)Next create the metaclass and override __prepare__

class ProhibitDuplicatesMeta(type)

@classmethod

def __prepare__(mcs, name, bases):

return OnShotClassNamespace()Next derived class from new metaclass

class Dodgy(metaclass=ProhibitDuplicateMeta)

def wouldnt_happend_in_cpp(self):

return "first method"

def wouldnt_happend_in_cpp(self):

return "second method"Summary of Functions

Further reading might be to look at

- __prepare__(mcs, name, bases, **kwargs) must return a mapping to hold namespace contents

- __new__(mcs, name, bases, namespace, **kwargs) must return a class object

- __init__(cls, name, bases, namespace, **kwargs) must configure a class object

- __call__() on metaclasses is athe instance constructor

Descriptor Revisited

To improve the descriptor example above we can add a metaclass so that the Positive class does know the name of attribute when reporting an error.

Create metaclass to support this

class DescriptorNamingMethod(type):

def __new__(mcs, name, bases, namespace):

for name, attr in namespace.items():

if isinstance(attr,Named):

attr.name = name

return super().__new__(mcs, name, bases, namespace)Create a class to hold the name of attribute

class Named:

def __init__(self, name=None):

self.name = nameDerive Positive Descriptor class from this to have Named attribute and change error messages to use it.

from weakref import WeakKeyDictionary

class Positive(Named):

def __init__(self, name=None):

super().__init__(name)

self._instance_data = WeakKeyDictionary()

def __get__(self, instance, owner):

return self._instance_data[instance]

def __set__(self, instance, value):

if value <= 0:

raise ValueError)"Value {} {} is not positive".format(self.name, value))

self._instance_data[instance] = value

def __delete__(self, instance):

raise AttributeError("Cannot delete attribute {}".format(self.name))Finally the only change required to the application class is to change the metaclass to be our new class.

class Planet(metaclass=DescriptorNamingMeta):

def __init__(self

....Abstract Classes

Intro

This is very involved and needs further investigation. There are virtual abstract methods where the metadata is in common and standard abstract where they are directly derived from the class

C#/C++ bit

To prevent abstract class being instantiated you can use the @abstractmethod decorator.

class Test

@abstractmethod

def abstract_method1(attr1):Improvements to the Temperature class

Using the @invariant decorator above works fine for one decorator but fails for multiple. e.g.

@invariant(below_absolute_hot)

@invariant(above_absolute_zero)

class Temperature:

...This is because the second (top) decorator is not seen as a property. Further investigation would be need to explain why. Here is the solution

from abc import ABC, abstractmethod

class PropertyDataDescriptor(ABC):

@abstractmethod

def __get__(self, instance, owner):

raise NotImplementedError

@abstractmethod

def __set__(self, instance, value):

raise NotImplementedError

@abstractmethod

def __delete__(self, instance):

raise NotImplementedError

@property

@abstractmethod

def __isabstractmethod__(self, instance):

raise NotImplementedError

# Virtual Class

PropertyDataDescriptor.register(property)Change InvariantCheckingPropertyProxy to inherit from this

class InvariantCheckingPropertyProxy(PropertyDataDescriptor):

def __init__(self, referent, predicate):

self._referent = referent

self._predicate = predicate

def __get__(self,instance,owner):

if instance is None:

return self._referent

result = self._referent.__get__(instance,owner)

if not self._predicate(instance):

raise RuntimeError("Class invariant {!r} violated for {!r}".format(self._predicate.__doc__,instance))

return result

def __set__(self,instance,value):

result = self._referent.__set__(instance,value)

if not self._predicate(instance):

raise RuntimeError("Class invariant {!r} violated for {!r}".format(self._predicate.__doc__,instance))

return result

def __delete__(self,instance):

result = self._referent.__delete__(instance)

if not self._predicate(instance):

raise RuntimeError("Class invariant {!r} violated for {!r}".format(self._predicate.__doc__,instance))

return result

# Added __isabstractmethod__

def __isabstractmethod__(self):

return self._referent.__isabstractmethod__Finally change the invariant_checking_class_decorator to look for PropertyDataDescriptors instead of property

def invariant(predicate):

def invariant_checking_class_decorator(cls):

# For each method name we validate

method_names = [name for name, attr in vars(cls).items() if callable(attr)]

for name in method_names:

_wrap_method_with_invariant_checking_proxy(cls, name, predicate)

# For each property name we validate

property_names = [name for name, attr in vars(cls).items() if isinstance(attr, PropertyDataDescriptors)]

for name in property_names:

_wrap_property_with_invariant_checking_proxy(cls, name, predicate)

return cls

return invariant_checking_class_decoratorPackages

Packages

Python finds packages by looking at sys.path. You can see this by doing

import sys

sys.path

# For entry 0

sys.path[0]

# To add you can

sys.path.append('/mypath');Another approach is to add your path to PYTHONPATH

export PYTHONPATH=$PYTHONPATH:/mypathMake a Package

mkdir -p /mypath/reader

touch /mypath/reader/__init__.pyFor a simple reader class the contents of __init__.py may be (absolute)

from reader.reader import ReaderFor a simple reader class the contents of __init__.py may be (relative)

from .reader import ReaderControlling whats imported

You can do this by specifying the __all__ content. Looks like a def file in windows dlls. e.g.

from reader.compressed.bzipped import opener as bz2_opener

from reader.compressed.gzipped import opener as gzip_opener

__all__ = ['bz2_opener', 'gzip_opener']Namespace packages

These are packages split across to directories and the root directories do not contain a __init__.py. Importing namespace packages

- Python scans all entries in sys.path

- if a matching directory with __init__.py is found, a normal package is loaded

- if foo.py is found then it is loaded

- Otherwise, all matching directories in sys.path are considered part of a namespace package

path1

|

--split_farm

|

-- bovine

|

-- __init__.py

-- common.py

-- cow.py

-- ox.py

path2

|

--split_farm

|

-- bird

|

-- __init__.py

-- chicken.py

-- turkey.pyExecutable Directory

You can make a executable by providing a __main__.py in the directory.

project

|

-- __main__.py

-- project

|

-- __init__.py

-- stuff.py

-- setup.pyYou can then run the code with

python3 readerZipping up the directory and it can be distributed as python treats zips a directories. e.g.

python3 reader.zip